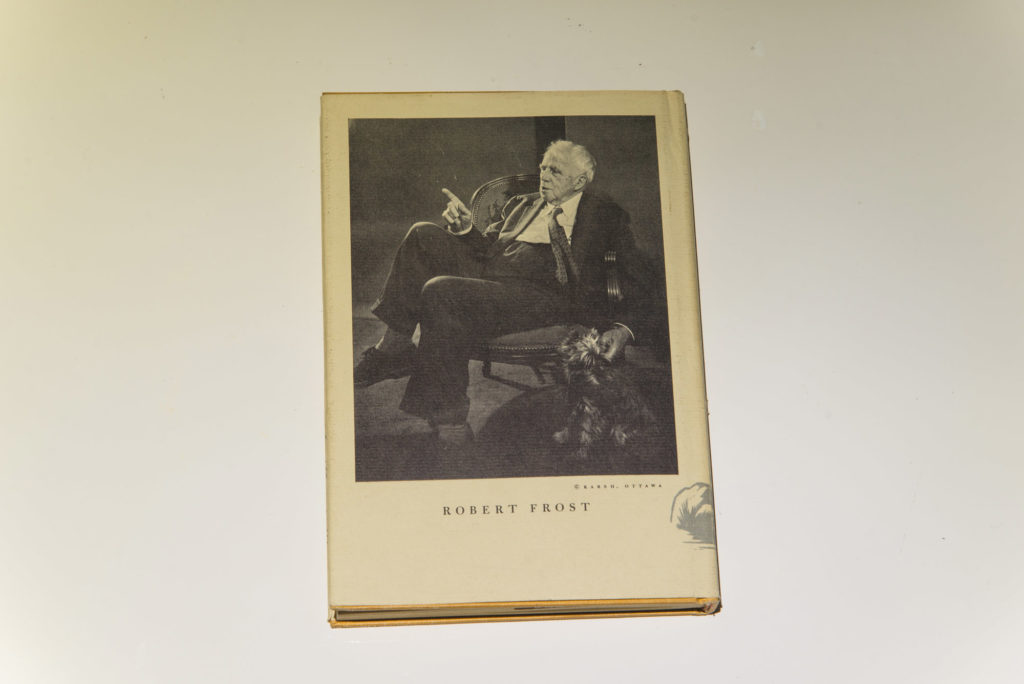

Time, Furtive Glances and Banality: a discussion of Silas Fong’s early works

Anthony T. K. Yung

2010

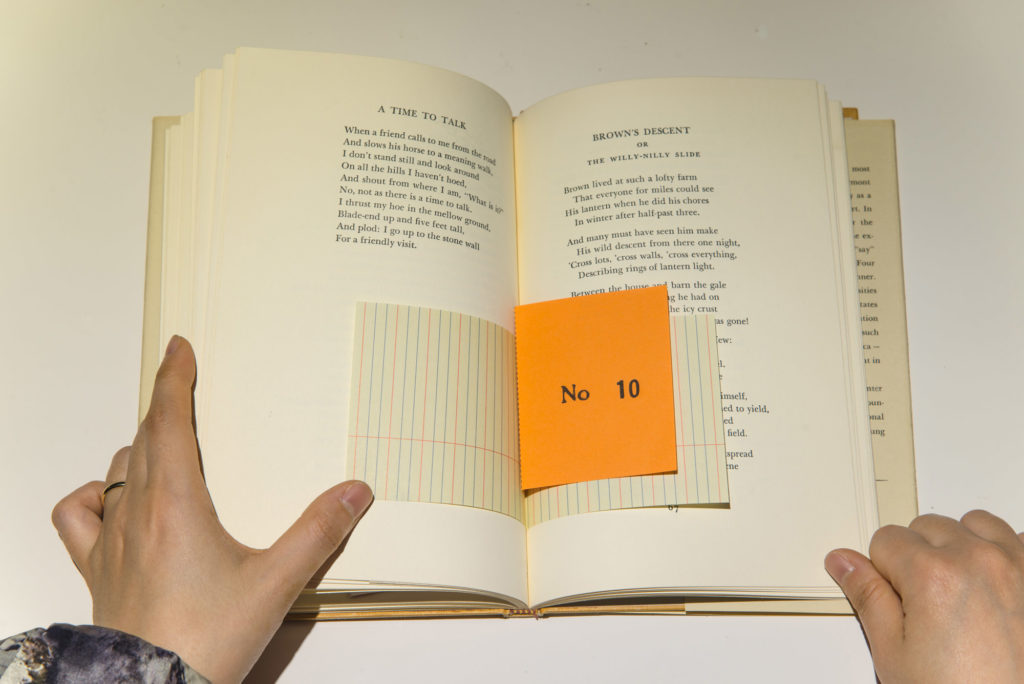

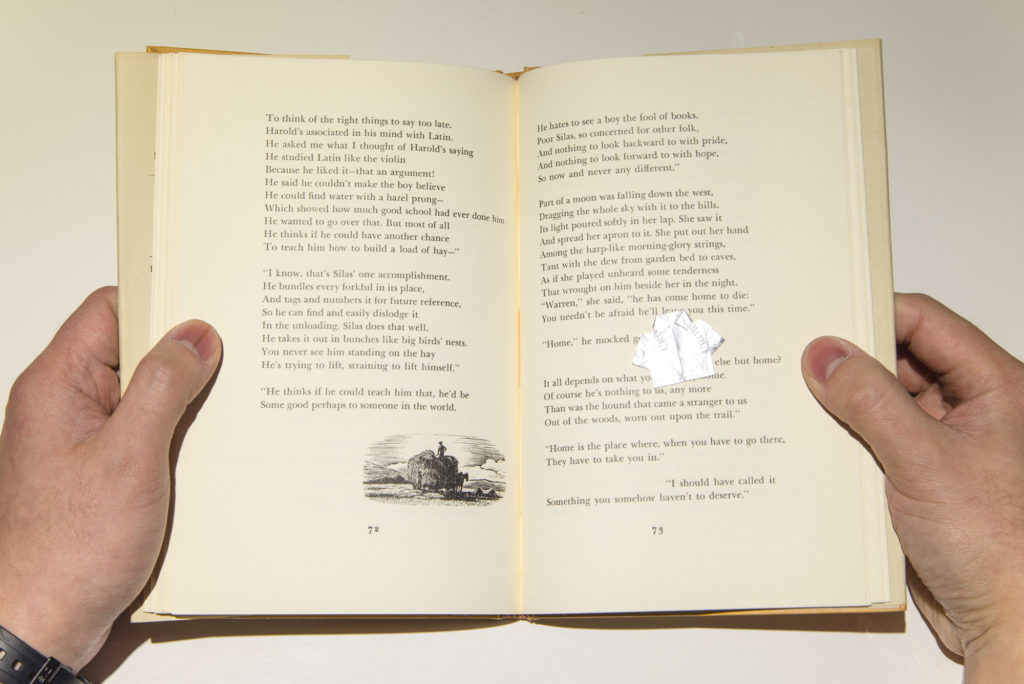

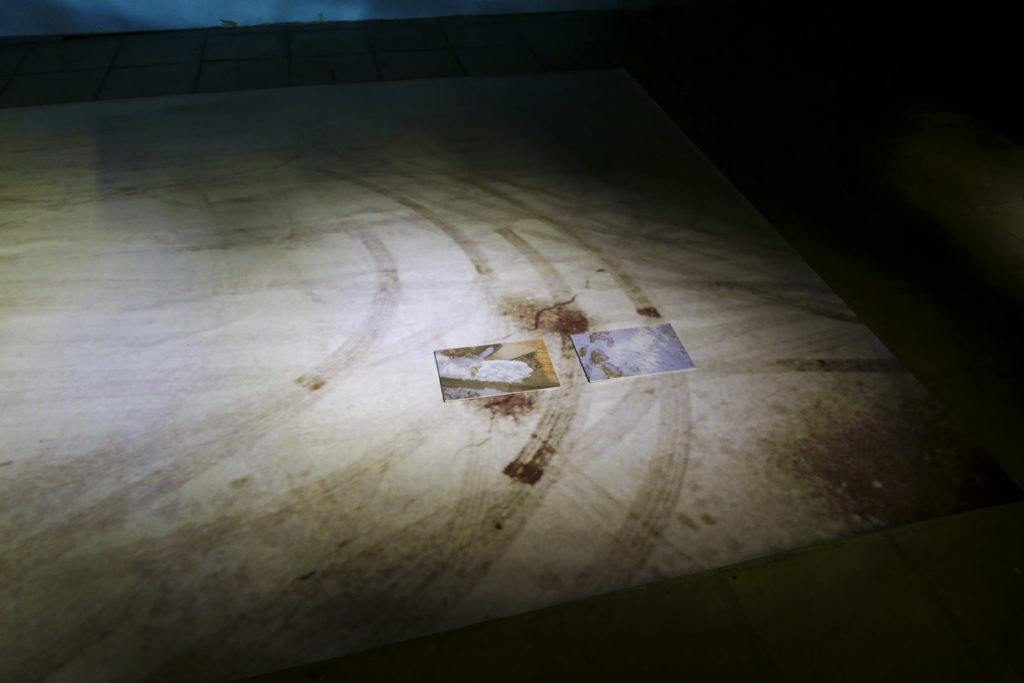

“Stolen Times for Sale”

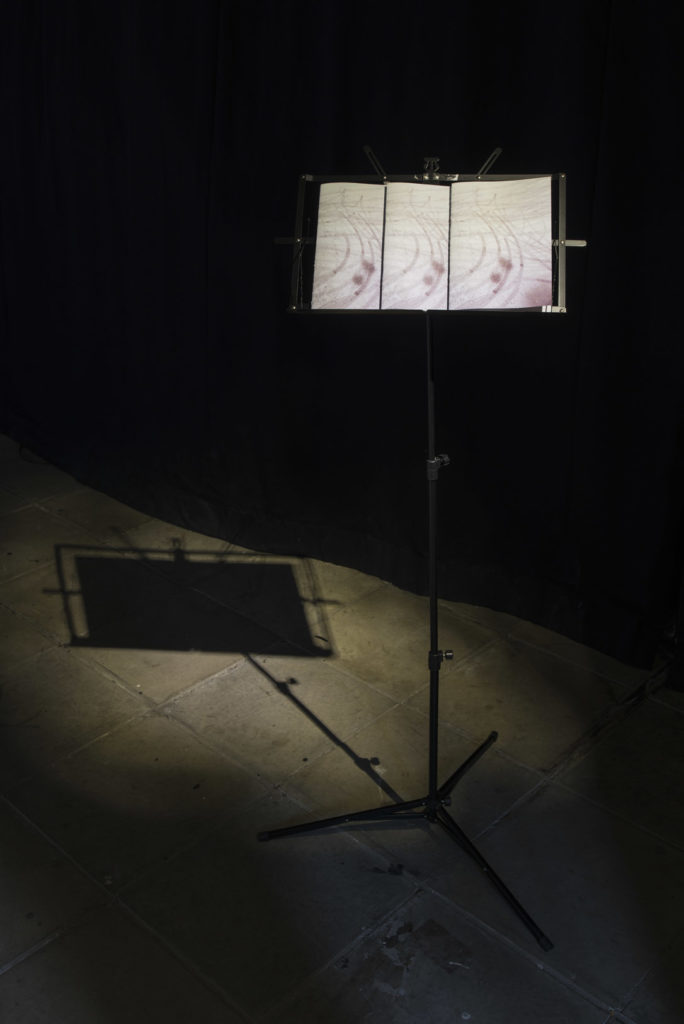

“Stolen Times for Sale” is a game of conceptual switcheroo. During the morning rush, Silas Fong pushed the hold button in the elevator of a Hong Kong high-rise apartment building. He filmed the fleeting six or seven seconds between the opening and closing of the doors. He then sold these dozens of six and seven second segments at a price determined by the number of people in the elevator, their expressions and their responses. Each segment is sold only once. The sold segment of video is replaced with a text on screen [Sold – XX Seconds for $XX]. When sales are good, and “time” is sold out, all that remains of the work is a textual record of the length and sale price of each segment.

This work has attracted attention in so far as it purports to not only steal a fleeting moment, but then sell it. It asserts the power to challenge the absolutism of time. However, what the artist is selling is not to time, but images. On that morning, seconds of time are stolen from the elevator passengers (the artist’s put-upon neighbors), time that should not have been lost in this way and which can never be wrested back. What has been sold is simply the image of the process of that theft, and not the time itself. The result is that those blameless few seconds now belong to no one: neither to the artist, nor to the buyer.

At this point we have already perceived that the conceptual switcheroo involves the concepts of “time” and “image.”

“Sale” is the work’s other central concept. Because images are reproducible, buyers and collectors of video art have been hesitant to enter the market. But in “Stolen Times for Sale,” the videos are only being sold in the name of “time.” The sale of the video makes effective use of the sense of absolute singularity that is associated with time, and is, in this way, seemingly effective at taking the measure and establishing the value of video art.

Thus, the structure of the work is established in the following way: wildly pushing elevator buttons is a favorite mischief of children in Hong Kong, and dull moments spent waiting for and riding in elevators–time spent in impatience–are also an unavoidable experience of Hong Kong life. Silas Fong turns these authentic experiences into an artistic subject, a game of logic, and uses the conceptual obfuscation of the artwork to package apparently reasonable products.

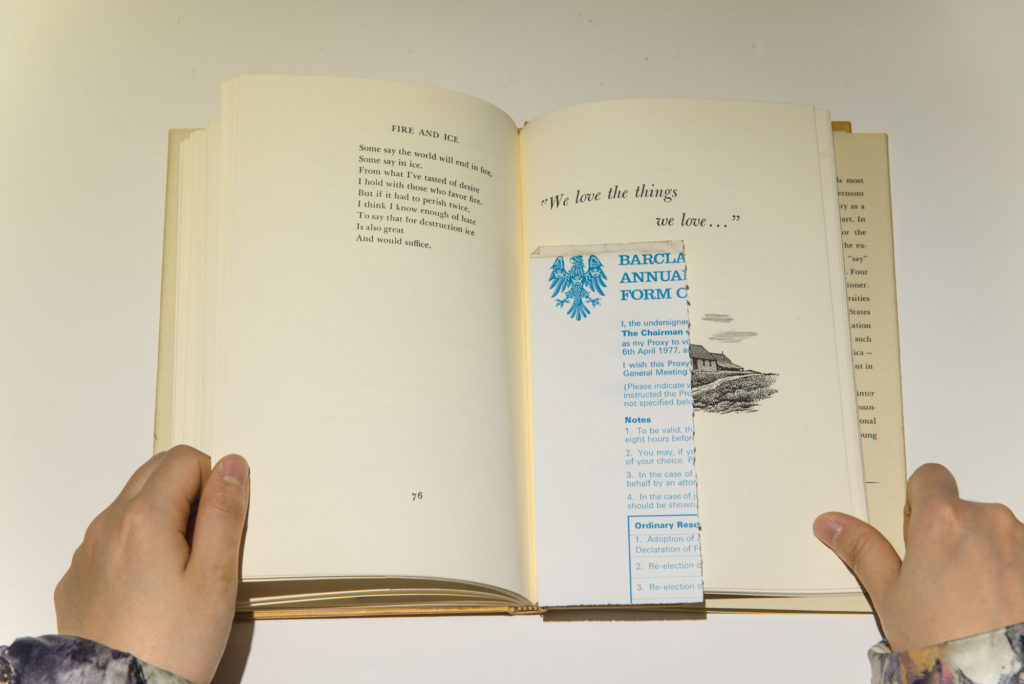

“Following strangers”

People continue to advocate for privacy, and privacy protections have been enshrined into law. At the same time, we can not wait to engage in performances of the self and to violate each other’s privacy. Facebook has easily surpassed Google as the world’s most popular website. Compared to Facebook, Google is but a serious, just and trustworthy librarian! When people log into Facebook, do they sense that they have now been placed beneath an infinite series of eyes? “Friends” on Facebook are uninterruptedly connected. Friends always have friends, and these “friends of friends” fall far outside the limits of our imaginations. They can be someone who you will never meet in your life, or they can be someone who is greatly offense to you. The eyes of “friends of friends” are the eyes of the big other, the eyes of the world. Deeds and images that you might rather not have made public can be posted at any time to Facebook by people who know you (not “friends,” but people who merely “know” you). The degree to which your precious privacy has been unveiled to the world will be unknown to you, let alone within your power to stop.

What is frightening about Facebook is that even if you do not participate, you can not avoid it. It’s primary driver is something that everyone shares in common: an objectless curiosity, a kind of voyeuristic tendency, a continually growing and insatiable desire, one that exists, in particular, in the virtual world of the internet.

Silas Fong’s work “Following Strangers” is a self-made, web-based platform, where he gathers account information of interest to him from users of Facebook and other social media platforms, and where he cites his reason for his interest in this person, his impressions of him/her and his reason and motivation for wanting to add them. Here, the artist is taking on the role of voyeur and surveiler/follower, and, at the same time, attempts to explore the background motivations for surveilling/pursuing/following these people. In this inverted social media platform, the focus is not on whether the photos and information from these strangers is truly interesting, but rather the disclosure of the psychic motivation of surveilling/pursuing/following strangers. For the most part, these so-called “motivations” are dull and banal, and reveal, to a greater or lesser extent, that in social media space, forming “real” relationships with strangers is beside the point, and what is most important is that when taking a furtive glance into the world of strangers, our curiosity is being continually nurtured.

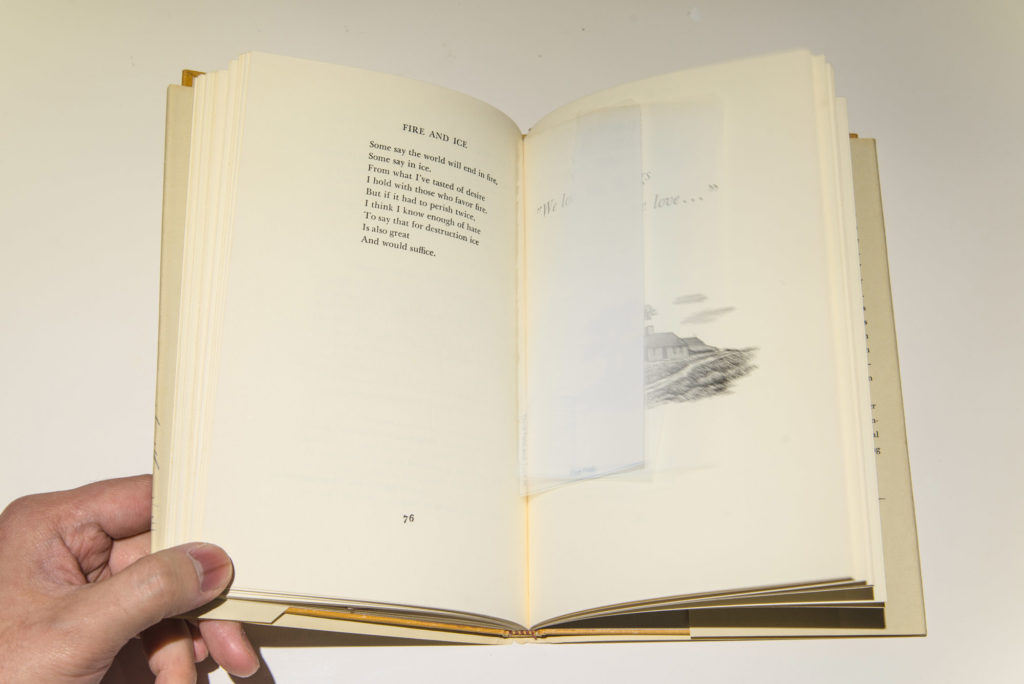

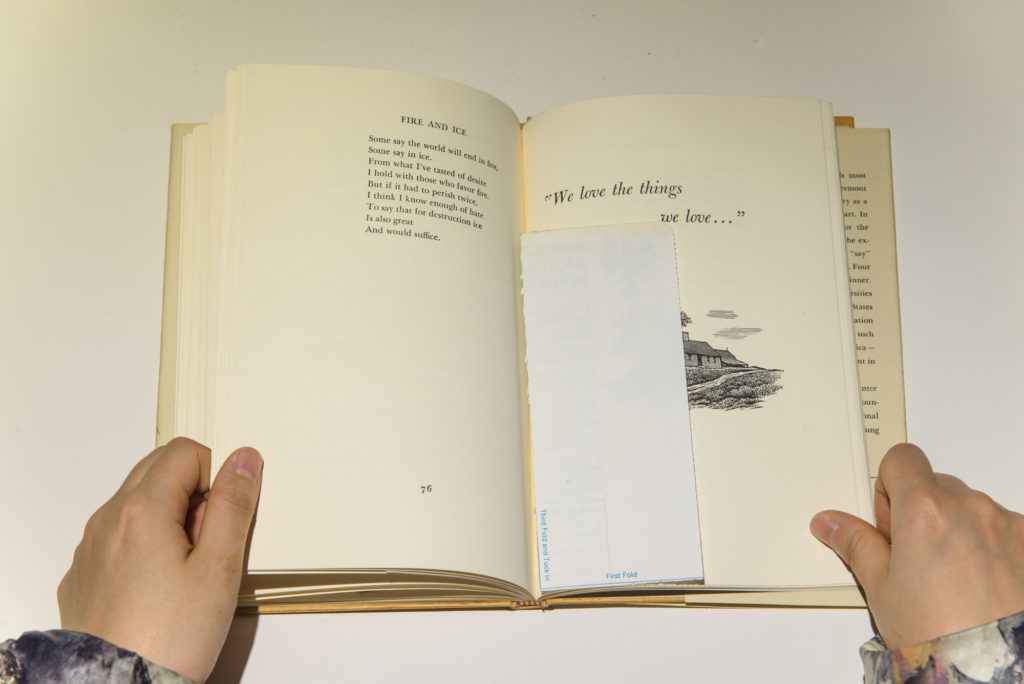

Staring, being stared at, and the disappeared starer

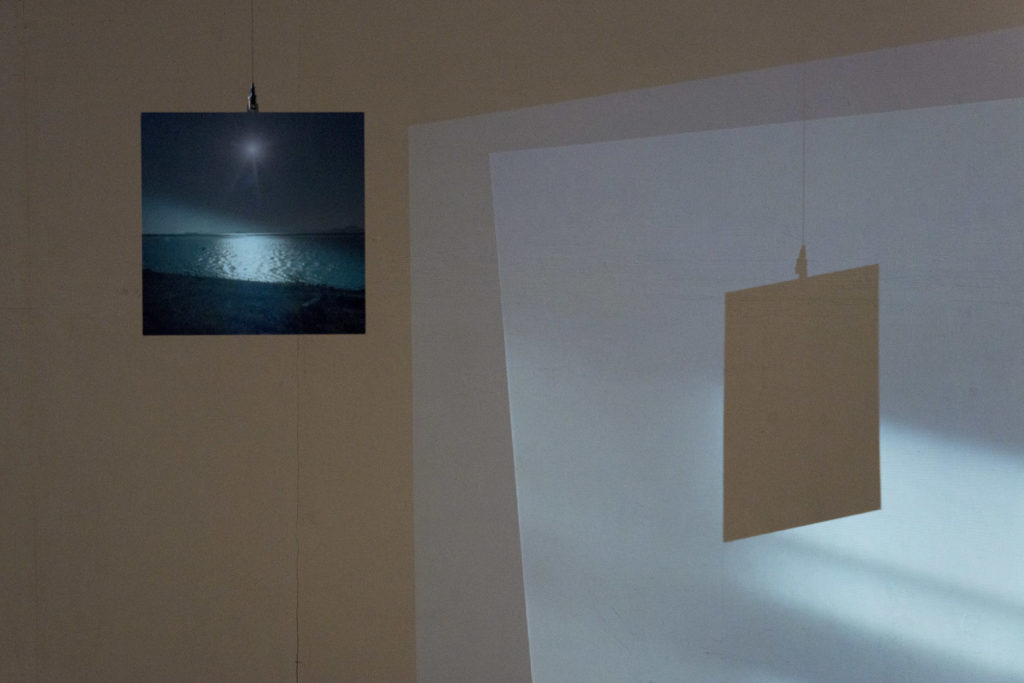

The work “In some seconds” is the artist’s documentation of the roadside scenery that passes over the course of a bus route. Throughout the recording, passersby cast their curious glances towards the lens. While in “Waiting,” the artist takes surreptitious pictures of the expressions of people waiting in Times Square. The installation of “In some seconds” is highly designed: it reproduces the visual experience of riding on a bus, which has no difficulty in attracting the viewer’s formalistic interest. The latter, we can easily place the latter within the urban documentary photography tradition of Walker Evans and Helen Levitt.

In fact, both works have developed around a topic of continuous interest for the artist. Everyday strangers appear in “In some seconds.” Their visages, expressions and gazes are videographic documentation of a transient moment in the rush of daily life. “Stolen Times for Sale” is concerned with fundamentally the same topic. “Stolen Times for Sale” forcibly interrupts people’s elevator journey to attract their gaze. When viewing, “In some seconds,” we can not be sure what it is exactly that is attracting the bystander’s gaze. Fascinatingly, when we view the work, we substitute ourselves for the subject of the staring, and imagine the self through the gazes and expressions of those strangers. In other words, other people are mirrors.

When compared to “In some seconds,” “Waiting” is far less grand in terms of subject and skill. The people waiting at Times Square in Causeway Bay are everyday people, strangers. They are unoccupied. Because their pictures have no particular significance as social documentary, these people can function as pure aesthetic objects. And because these were taken surreptitiously, the gazer disappears, and again we walk into this paradox: is the focus of this work on the aesthetics of the object or is it the subjective feeling of pleasure produced from voyeurism? Here, Silas Fong is in the process of simplifying the form and conceptual structure of his work, attempting to utilize an exceedingly banal attitude to represent the banality of people.

[Translated from Chinese by Jesse Robert Coffino.]