下載簡歷

English

方琛宇

1985年生於香港

現生活於香港及首爾

教學

2017- 韓國首爾中央大學藝術學院攝影系助理教授

學歷

2013-2015 德國科隆媒體藝術學院 – 媒體及純藝術

2010-2012 香港中文大學藝術系藝術碩士 (創作)

2007-2008 荷蘭阿姆斯特丹大學交流生

2005-2008 香港浸會大學(榮譽)視覺藝術文學士

個展

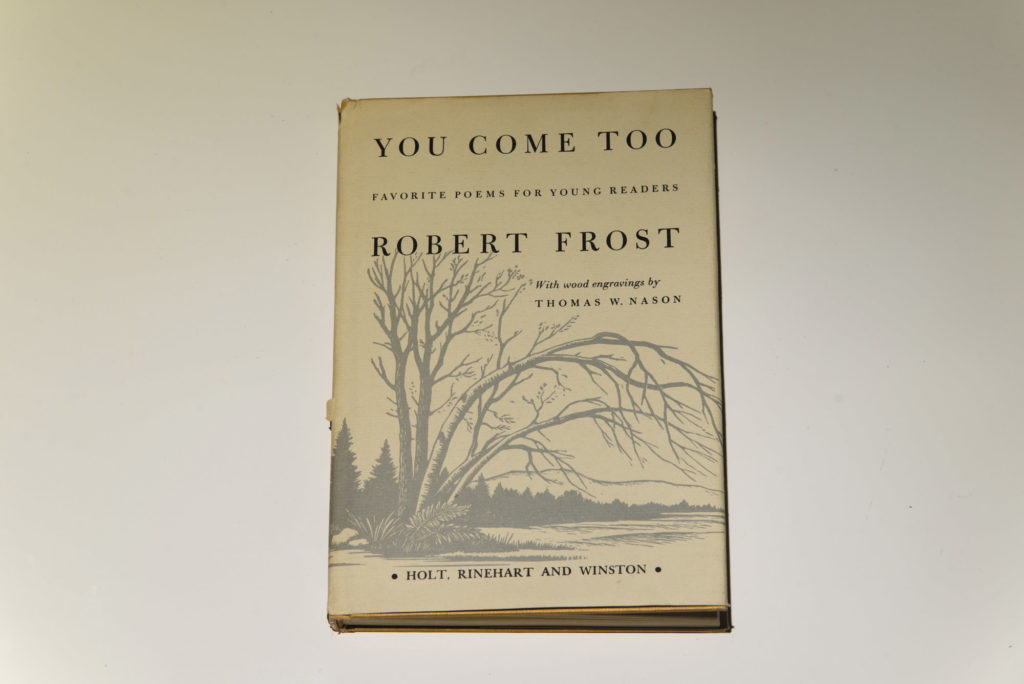

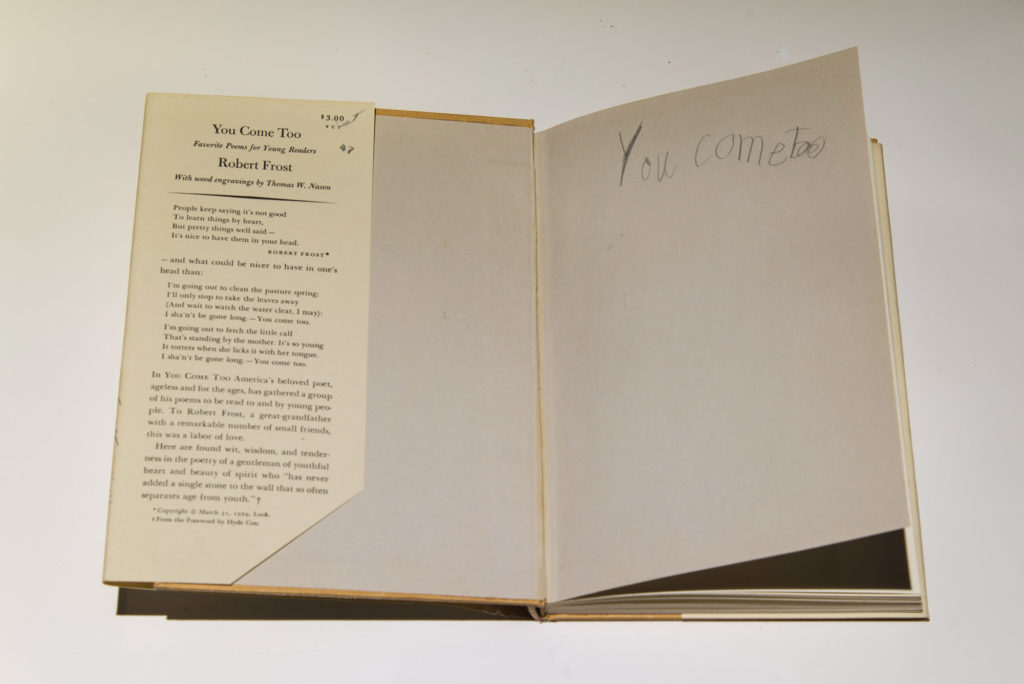

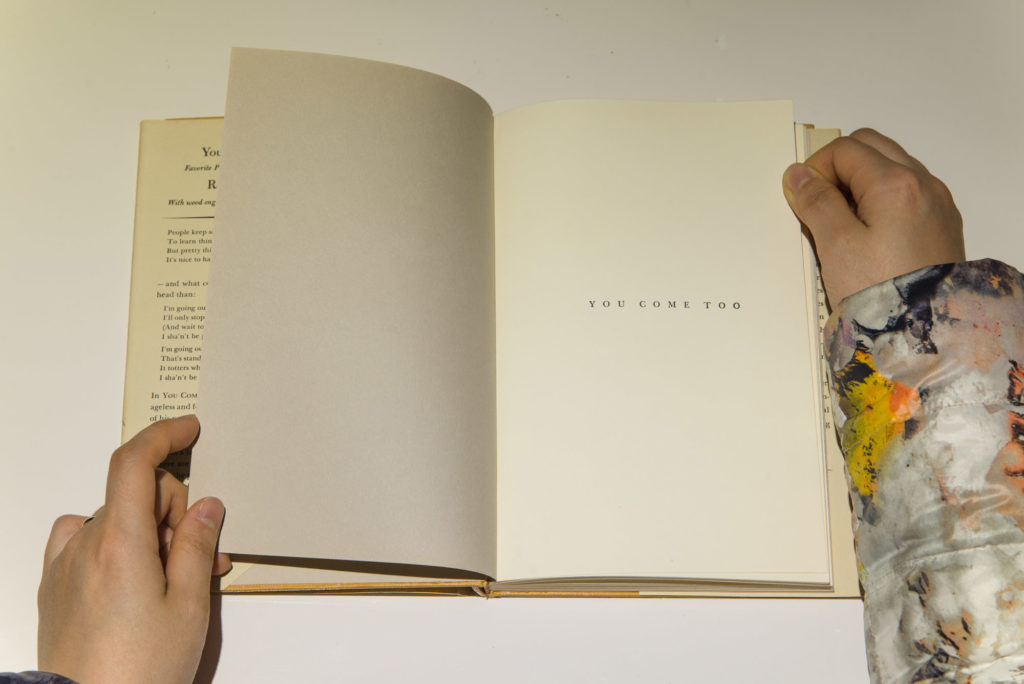

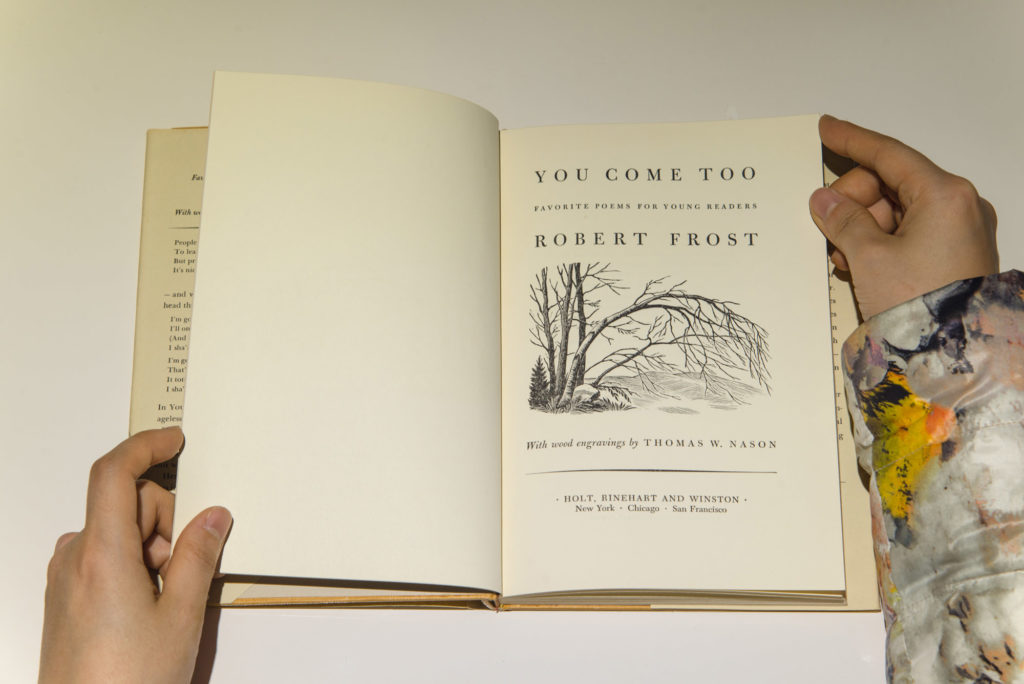

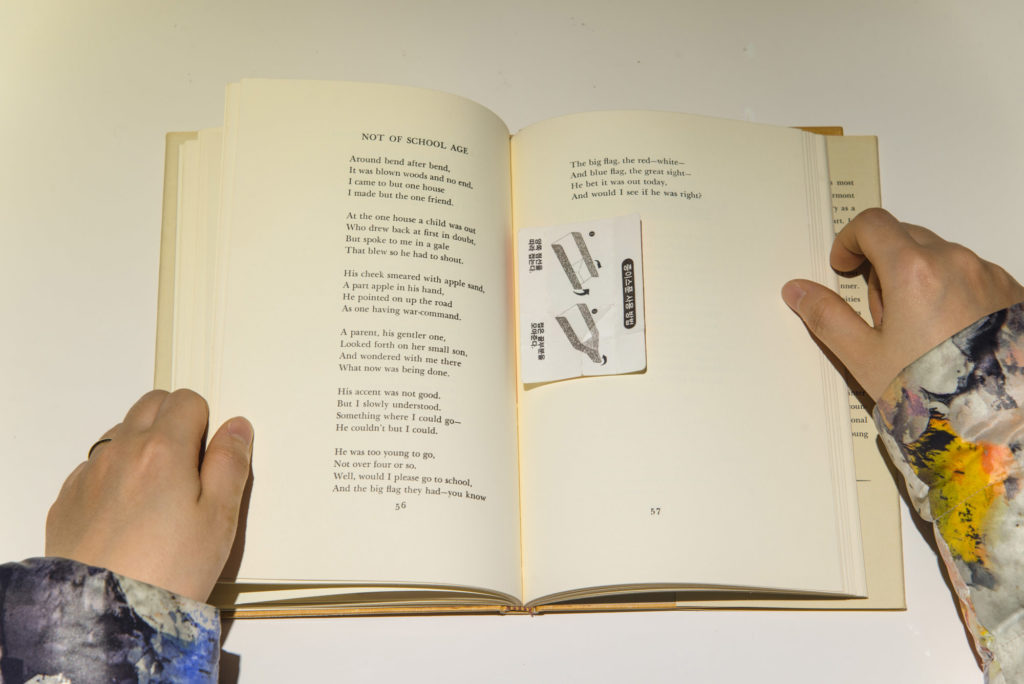

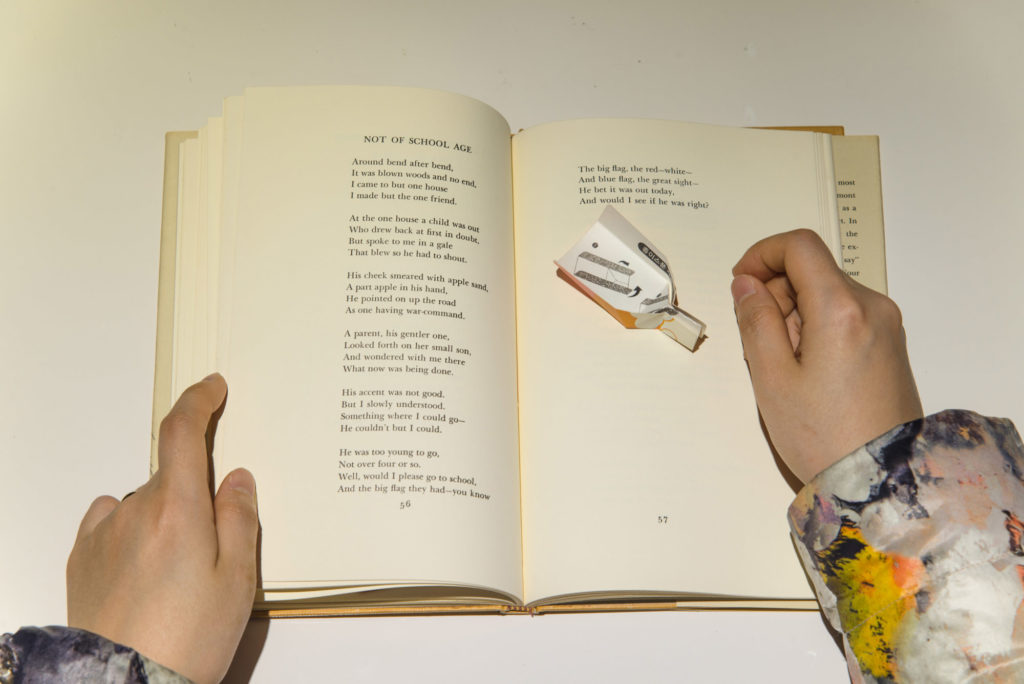

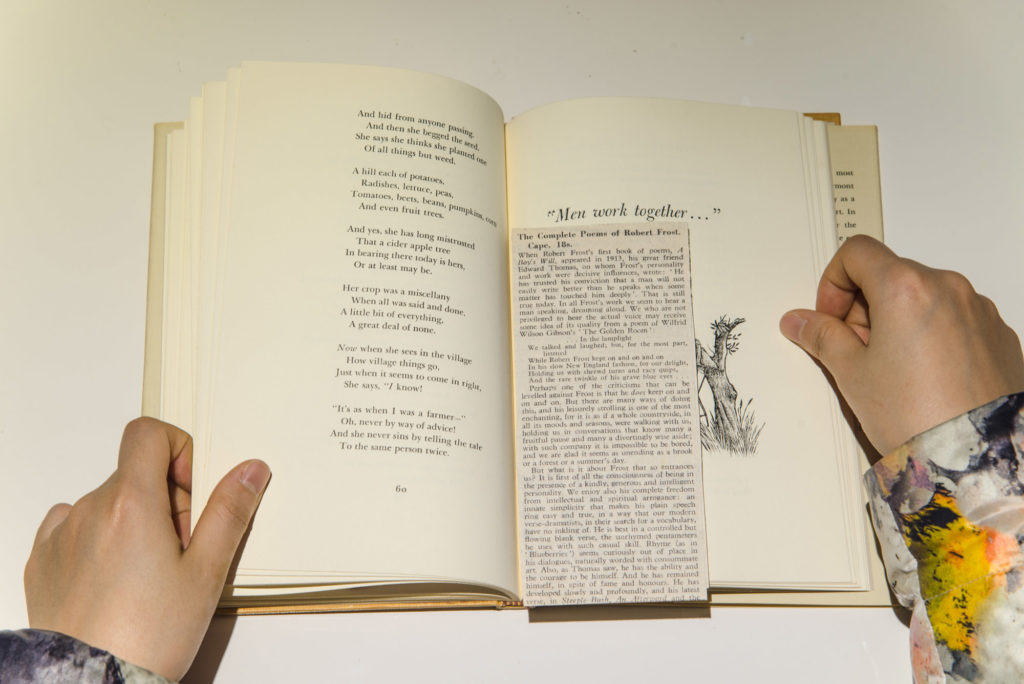

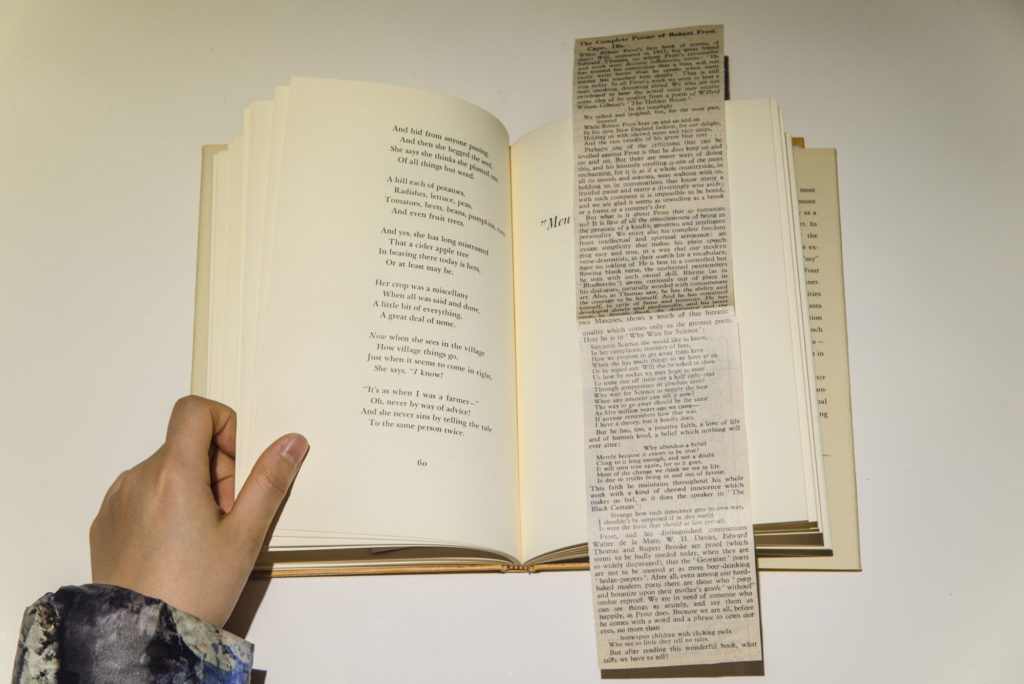

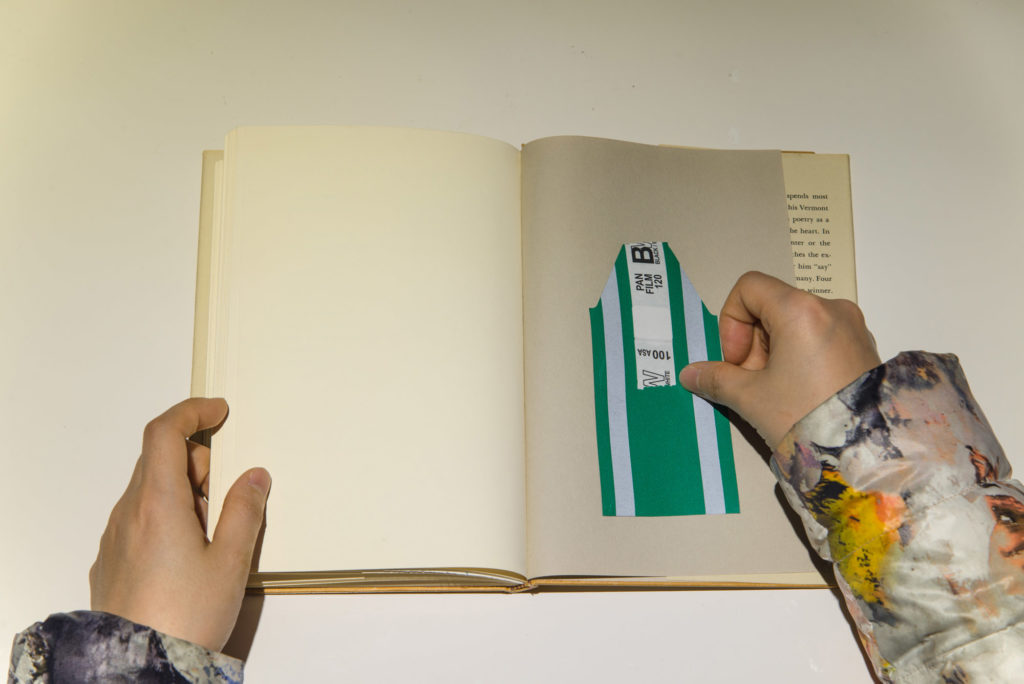

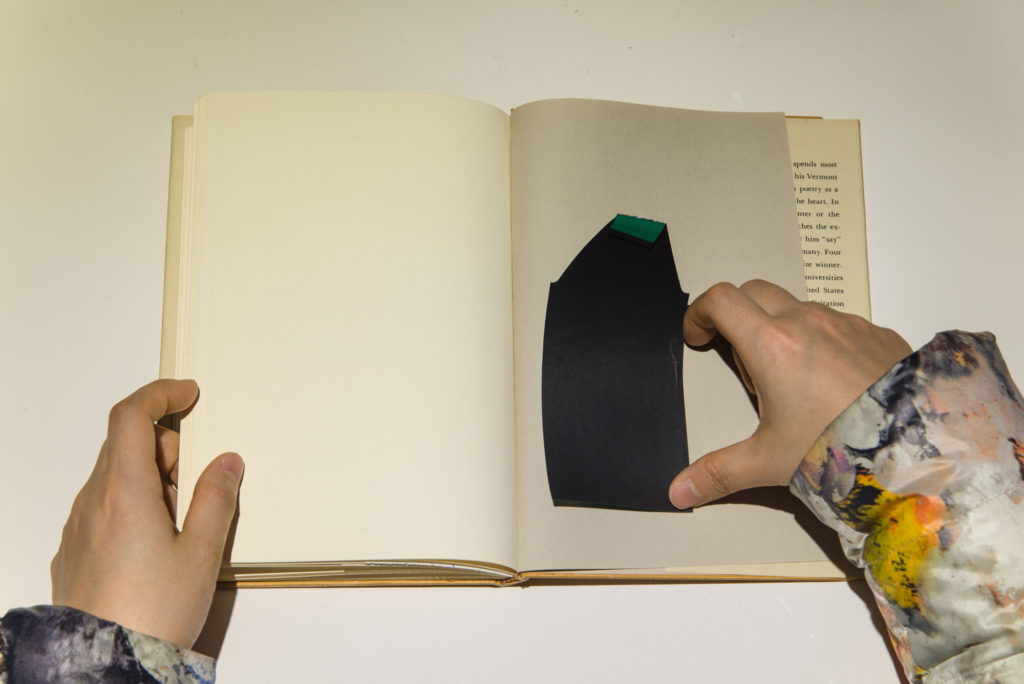

2017 雪夜林邊

香港錄映太奇

2016 沒有時間

釜山虹田藝術中心

2016 比哥羅米尼街316號

香港歌德學院歌德藝廊及黑盒子

2015 愛蝶灣6樓D室

德國科隆媒體藝術學院CASE攝影項目空間

2012 連續劇

廣州觀察社

2011 記憶障礙

香港安全口畫廊

2008 不知名 – 方琛宇首個個人展覽

香港牛棚藝術村藝術公社

聯展

2018 Once A God: The Myth of Future Refugees: Taehwa Eco-River Art Festival (Forthcoming)

韓國蔚山太和江公園

The Day the Gods Stop Laughing (Forthcoming)

香港都爹利會館

Housewarming

Better Than Company, Seoul

2017 蒼生前

韓國蔚山長生浦新津旅人宿

Up Close Yet Unfamiliar

韓國首爾AMC Lab

2017 鍾正, 方琛宇, 王思遨 (巡迴展出)

香港安全口畫廊

Folding / Unfolding: 流動攝影展

香港浸會大學視覺藝術院啟德校園

Me: Millennials

香港K11

「鏡外、鏡內」攝影展

香港K11 Chi 藝術空間

2016 時間測試: 國際錄像藝術研究展 (巡迴展出)

北京中央美術學院美術館;廣州紅磚廠當代藝術館

像素之後: 動漫美學雙年展2015-16

香港邵逸夫創意媒體中心

憂鬱體液

香港百呎公園

2015 低緯度的不透明

廣州畫廊

彼岸觀自在2:最好的時代,最壞的時代 ?

香港chi K11藝術空間; 上海瑞象館

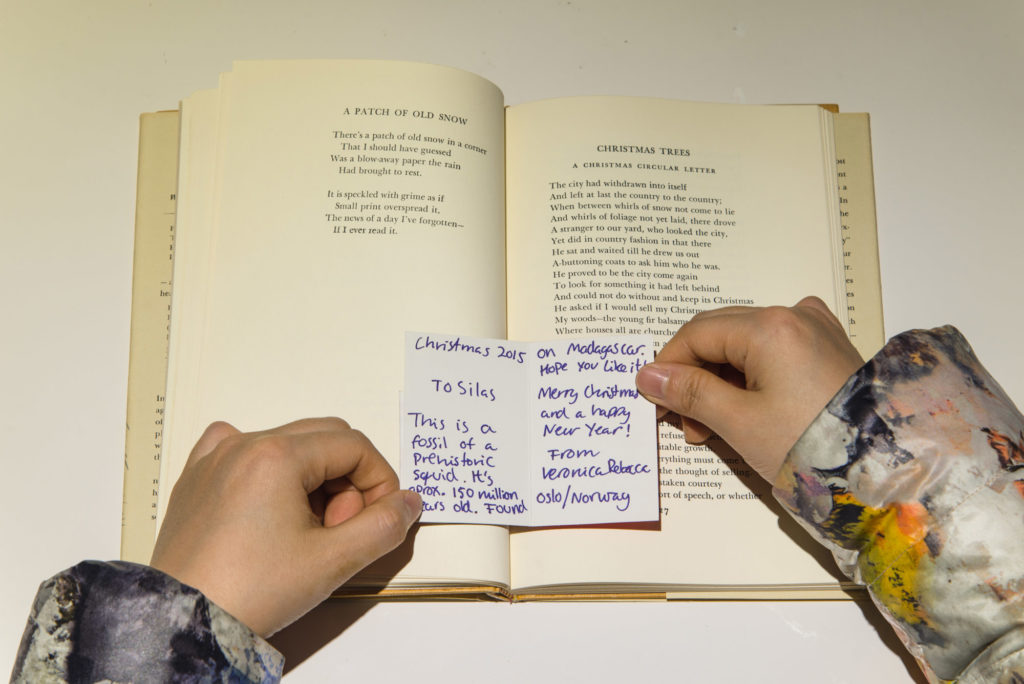

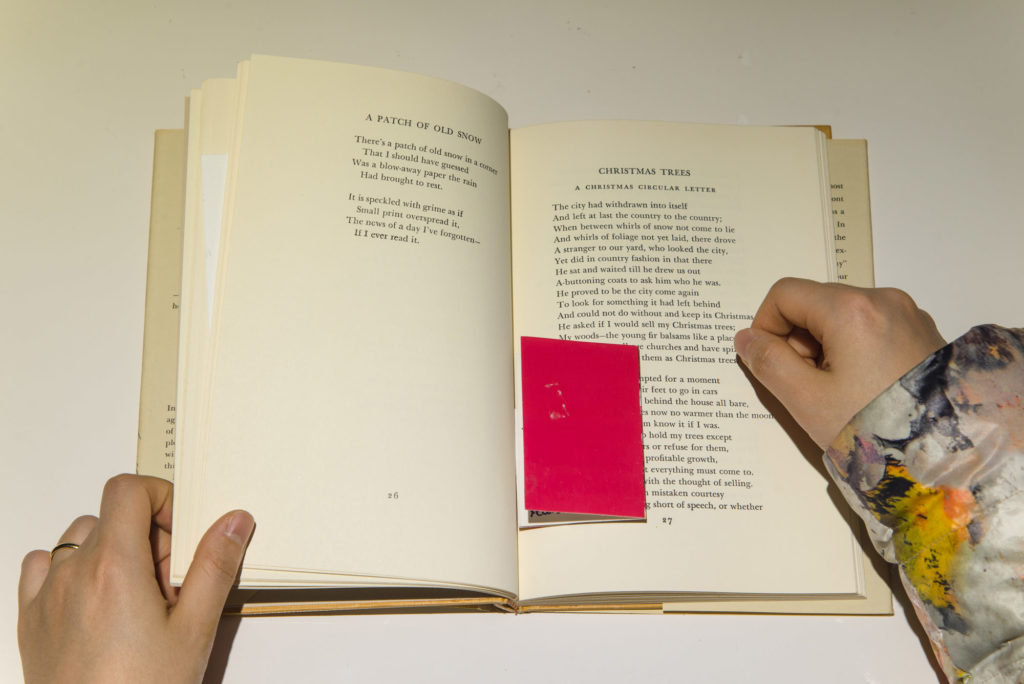

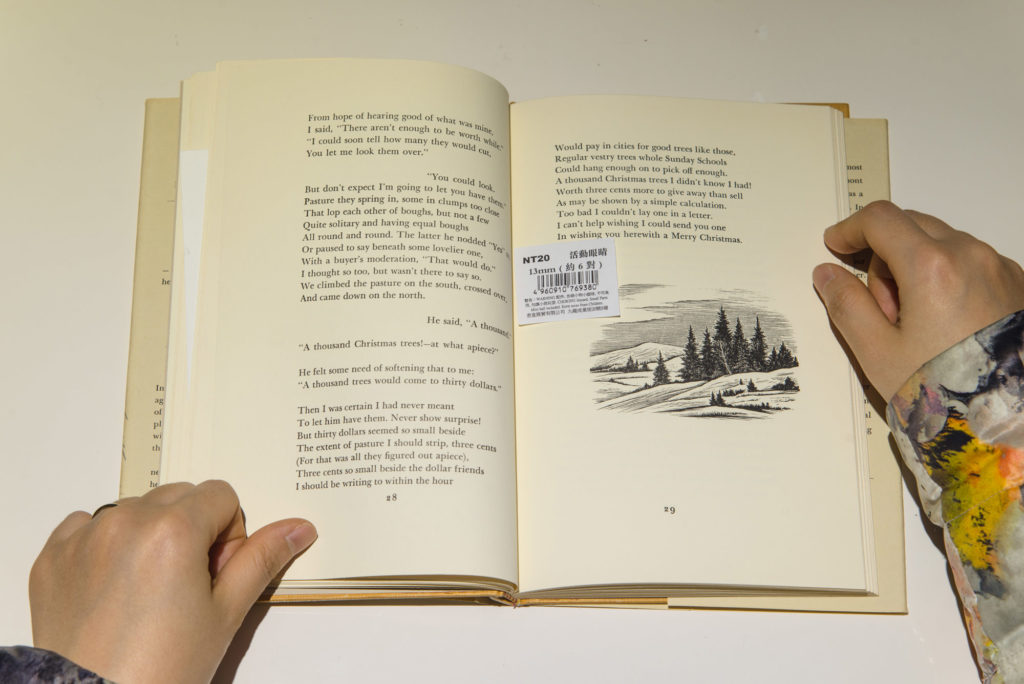

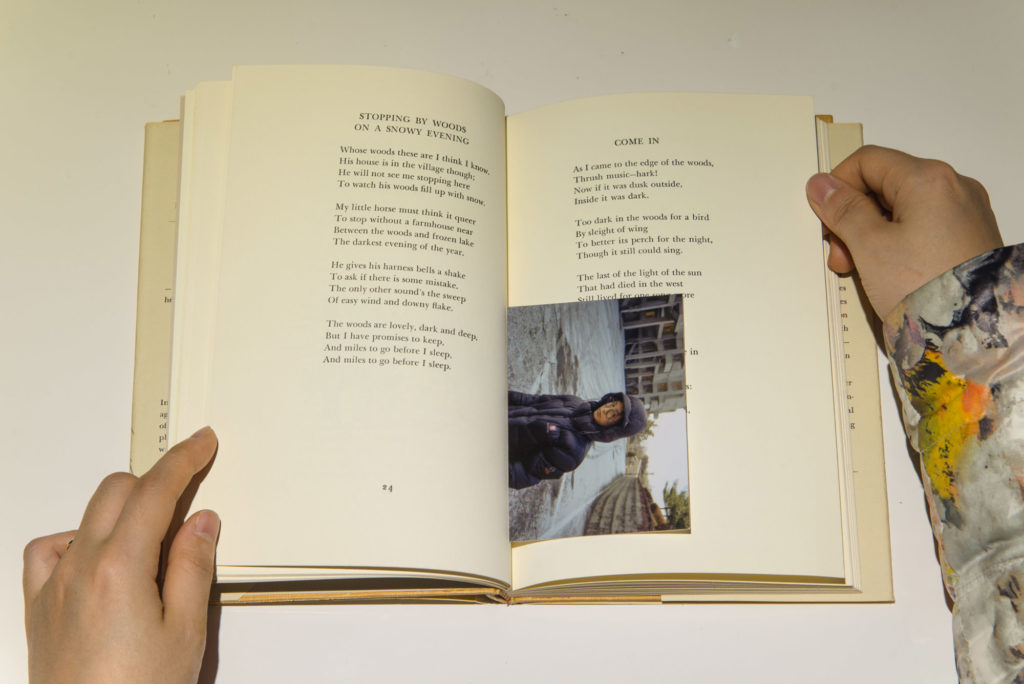

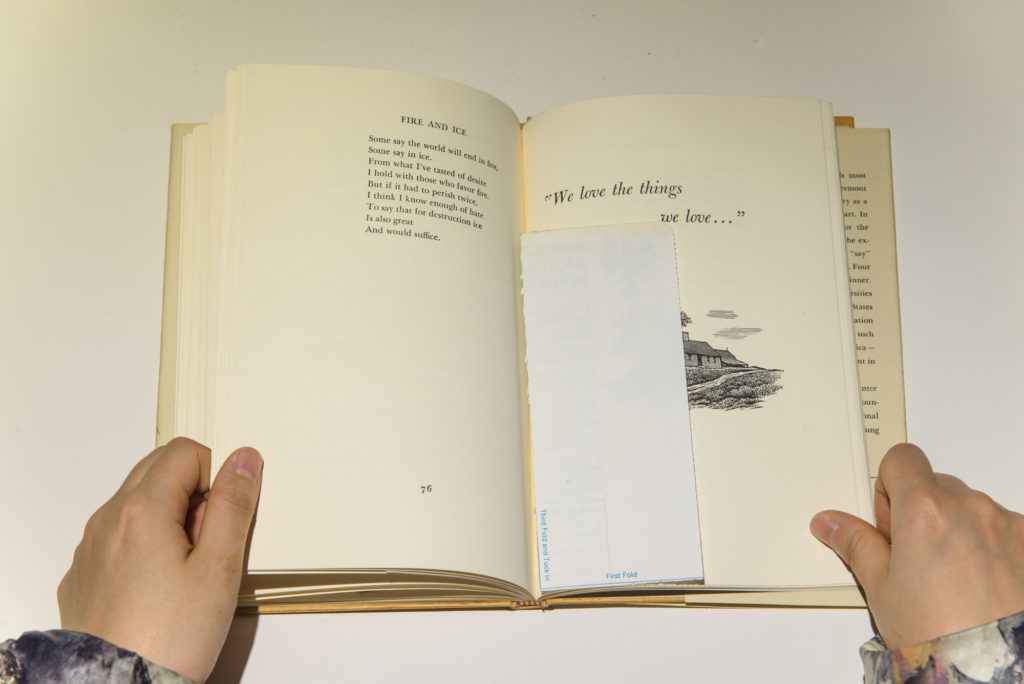

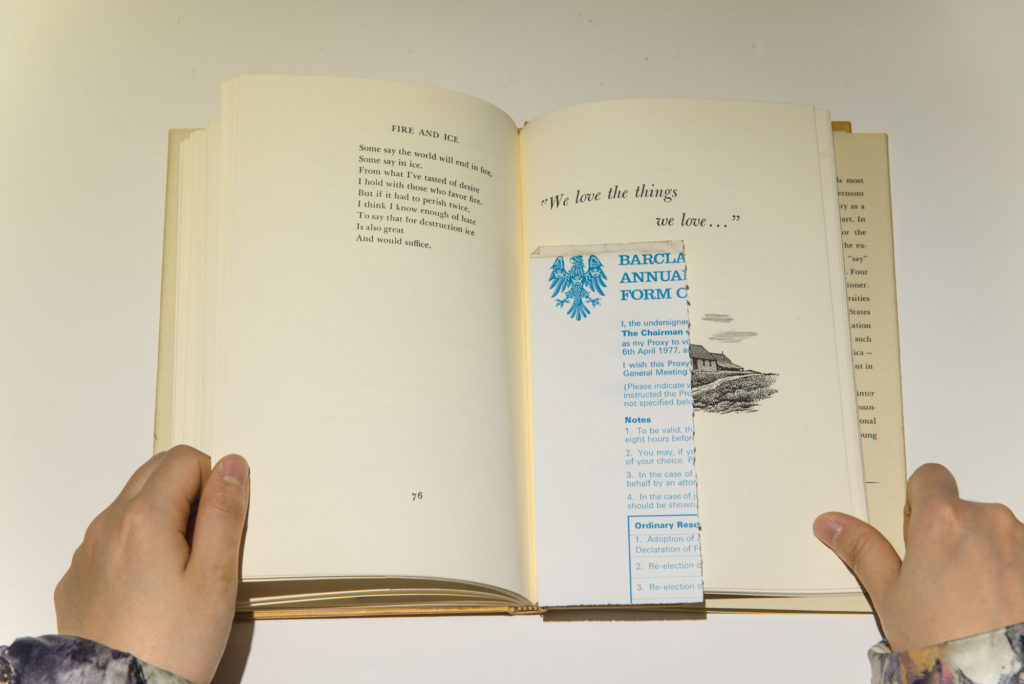

十五份邀請: 藝術書袋(以及裡面的物件)簡史

香港亞洲藝術文獻庫

侊動領域

台北當代藝術館

Rundgang

德國科隆媒體藝術學院

after/image

香港Pure Art Foundation

第二十屆ifva 互動媒體組入圍作品展

香港藝術中心包氏畫廊

2014 未来.自家制 – 新視野藝術節

香港大會堂展覽廳

alle berichten darüber – 紀錄攝影展

德國科隆媒體藝術學院CASE攝影項目空間

2013 德累斯頓媒體藝術節CYNETart

德國德累斯頓赫勒勞節慶劇院

微波國際新媒體藝術節2013

香港電影資料館

HARD WARE SOFT CORE

柏林team titanic

工作室開放展覽

德國柏林GlogauAIR

亞洲時基:新媒體藝術節 2013 – “微型城市”

美國紐約長島市NARS基金會

Hong Kong Eye

香港ArtisTree; 香港文華東方酒店

Sky++, 數碼社區藝術展覽

香港歌德學院畫廊

Moving on Asia: Towards a New Art Network 2004–2013

紐西蘭威靈頓市立美術館

Move on Asia—2002-2012亞洲錄像藝術展

德國卡爾斯魯厄藝術與媒體中心

2012 Hong Kong Eye – 香港當代藝術

英國倫敦Saatchi Gallery

Move on Asia 2012

韓國首爾Alternative Space LOOP

發明了發夢

香港勁草工作室

跑邊線─香港新媒體藝術展

台北索卡藝術中心

AVA x JCTIC

香港浸會大學CVA展覽廳

2011 Detour 2011: Use-less

香港荷李活道前己婚警察宿舍

Video Art For All – 國際錄像藝術節 2011

澳門東方基金會

Nightlight

荷蘭 Hoensbroek Greylight Projects

第十一屆首爾國際新媒體節

韓國首爾Media theater i-Gong; KT&G Sangsangmadang Cinema; Seoul Art Space-Seogyo; Post Theater;

Yogiga Expression Gallery; The Medium, Off’C; C cloud, Off℃

無序‧有序

丹麥哥本哈根 Netfilmmakers

香港錄映太奇

利物浦雙年展 2010 放映會

韓國首爾Alternative Space LOOP

2010 Experimenta Mostra De Videos – Homemade video from Hong Kong

巴西聖保羅SESC Campinas

利物浦 2010: Media Landscape, Zone East (巡迴展)

英國利物浦當代城市中心

英國倫敦韓國文化中心

工作坊:傳播的圖與轉譯的像

北京伊比利亞當代藝術中心

Move On Asia 2010: 封印於錄像中的時間 (巡迴展)

香港Para/Site藝術空間; 英國泰特現代美術館

韓國首爾Alternative Space LOOP

台北藝術博覽會2010

台北世貿中心

香港當代藝術雙年獎 2009

香港藝術館

擺渡

香港荷李活道前警察宿舍

2009 鏡子舞台

香港視覺藝術中心

凝視中, 事過境遷

香港agnés b.’s LIBRAIRIE GALERIE

擦身而過

香港YY9 畫廊

這是香港 (巡迴展)

奧地利維也納藝術廳; 台北關渡美術館;

香港Map Office; 西班牙馬德里Casa Asia;

德國柏林IFA Gallery; 英國伯明翰Eastside Projects;

德國漢堡subvision, subvision. art. festival. off.; 韓國首爾Alternative Space LOOP;

西班牙巴塞隆那Casa Asia, LOOP Festival 2009

城市藝穗

澳門塔石廣場

偽清白

香港奧沙觀塘

第十四屆ifva 互動媒體組入圍作品展

香港藝術中心包氏畫廊

Some rooms

香港奧沙觀塘

2008 Live Herring ‘08 – 媒體藝術展

芬蘭于韋斯屈萊藝術館

視界2.0 – 鏡像中國

德國柏林藝術大學大樓展廳

出爐 2008

香港牛棚藝術村藝術公社

Current, 畢業展

香港浸會大學視覺藝術院畫廊

Arrest – An exhibition of frozen time and space

香港牛棚藝術村N5 單位

2007 觀察與研究 – 裝置藝術展

香港浸會大學視覺藝術院畫廊

我不會觀賞它,卻只會用它 – 每天生活設計展覽

香港浸會大學視藝術院畫廊

極樂 – 聯校多媒體作品展

香港浸會大學視覺藝術院畫廊

2006 視覺藝術院開幕展

香港浸會大學視覺藝術院

表演及放映

2012 The Rising Stars of Asia – Hong Kong Epilogue (The Octavian Society 委約)

亞洲協會香港中心

2011 新銳舞台: 年輪曲

香港演藝學院劇場

2010 兒時情境

香港文化中心大堂

布賴恩.伊諾的機場音樂:當代音影實驗現場

葵青劇院黑盒劇場

2009 建築是……音樂對話

香港文化中心劇場

藝術家駐場計劃

2016 釜山虹田藝術中心

2016 香港油街實現藝術空間

2013 GlogauAir, 柏林

2011 Summercamp Electrified 2011, 比利時根特Timelab

客席講座

2013 Guest Speaker. Dept. of Cultural and Creative Arts, The Hong Kong Institute of Education

2012 Guest Speaker. Young Friends, Friends of the Art Museum, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

2012 NewNowNext – A Talk with Young Chinese Artists. Asia Art Pacific and Chambers Fine Arts of New York/Beijing

2012 Guest Speaker. Centre for the Arts, Student Affairs Office, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

2011 Portfolio Workshop. Visual Arts Axis, Academy of Visual Arts, Hong Kong Baptist University

2009 Guest lecturer and Workshops Hong Kong Visual Arts Centre

2009 Guest Speaker. (Hong Kong Contemporary Art Biennial Awards) Hong Kong Museum of Art

獎項、資助及收藏

2016 香港藝術發展局新苗資助

2016 香港民政事務局藝術發展基金(文化交流計劃)

2016 光州雙年展藝發局代表團

2015 第二十屆香港獨立短片及錄像比賽(媒體藝術組)入圍作品

2013 香港中文大學藝術系 高美慶教授藝術贊助基金

2010 四十驕子(40 under 40), 透視雜誌

2009 香港藝術館香港當代藝術雙年獎 青年藝術家獎

2009 第十四屆香港獨立短片及錄像比賽(互動媒體組)金獎

2008 澳門藝術館 中國行為藝術文獻收藏

2008 香港浸會大學視覺藝術院 畢業展傑出作品獎